I think I’ve heard it said that coaching an endurance athlete involves part science — part art. It’s a sentiment I broadly agree with, and for me, roughly translates to convincing the athlete to do the activity that will help them most on a given day. Successful coaching is obviously multifactorial and must combine knowledge of physiology with the personal ability to communicate with an athlete. As illustrated in Figure 1, the physical component could be — perhaps over-simply — described as the activity that delivers the most physiological progression. The non-physical — slightly more difficult to pin down — could be facilitating the athlete to do the required session and enabling them to believe it is the most suitable thing for them to do on any given day.

Figure 1. Successful coaching of an athlete combines the daily prescription of a session using knowledge of physiology alongside the personal ability to communicate with an athlete while appreciating the context.

When I think back to the most influential coaches I have worked with, they have stood out for their passion, commitment and nature. Additionally, it was their ability to give relevant and contextual advice, consistently and reliably, which, most importantly, ensured my trust in them, and led me to have real conviction in the advice they imparted and the sessions they set. I truly believe that my conviction in any given training intervention — the belief in its efficacy — was the most significant factor in its success.

Many people have described these non-physical, or human factors, as a science. They may be right. However I would describe the process of coaching as a purely scientific endeavour for another reason. It is, at its simplest, scientific discovery; observe, question, hypothesise, predict, test and then explain. This process of n=1 scientific discovery can, and should be, helped along by academic research. The correct research used in the right context can allow the most relevant hypothesis to be formulated, leading to accurate predictions and successful, testable outcomes. I imagine I’m not the only one to forget that the ultimate outcome is to go faster, or further, on race day, and not fall foul of Goodhart’s seemingly ubiquitous law; to just get better at the test.

The number of papers published on endurance sports seems to be exploding. And, so is their complexity. A quick search on a publication database shows 12,600 papers on Sport Science were published in the top 125 subject specific journals in 2010. This had increased to nearly 18,000 in 2020. However perhaps an even bigger explosion occurred in the amount of data we can collect from various wearables; from how far or fast we are moving, to the rate or total amount of work we are doing, to the effect that such work is having on our substrate metabolism, to body temperature, our lactate or oxygenation levels, and on it goes. Maybe the sensor is taking a measure of our movement and working out mechanical efficiencies, and/or looking for deficiencies. Possibly the wearable does many of these and tracks vital everyday metrics such as heart rate, respiratory rate and heart rate variability. Research seems to be published almost daily suggesting that, when much of this data is used in the right way, it can have a positive performance benefit.

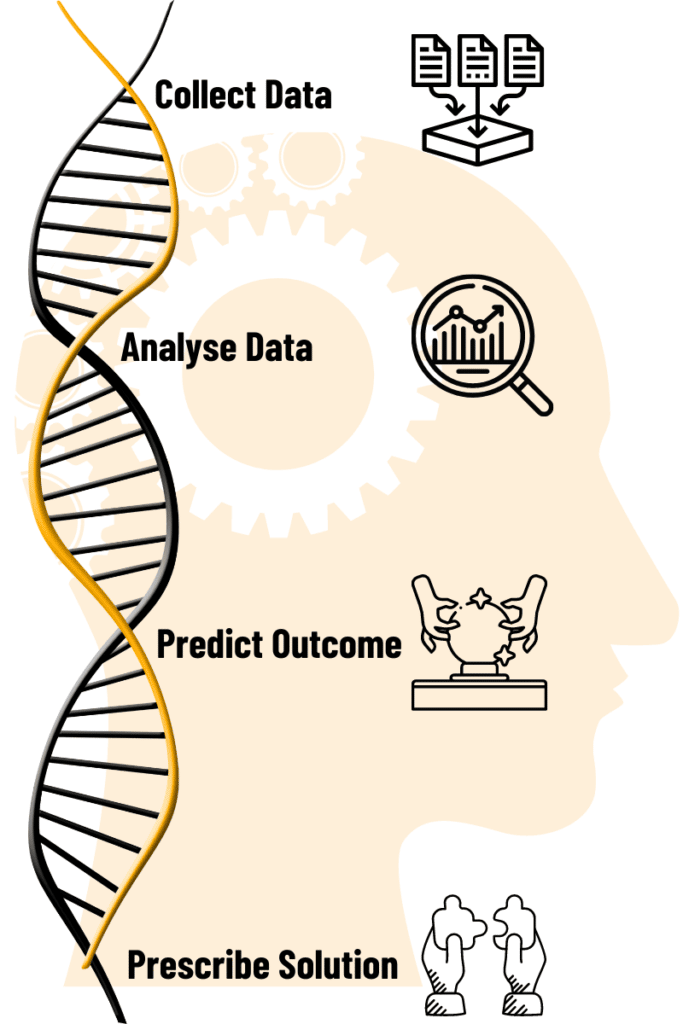

Collecting data is not difficult. And neither should be the process of training an athlete. Ockham’s razor, that that “the simplest explanation is usually the best one”, was drilled into me during school science classes. I’ve since learned however that Ockham’s razor is even more valuable in the context that simpler explanations are more easily falsified, and consequently, tested. Collecting and recording data is relatively easy, but analysing it is a bit more difficult. Making prescriptions from the analysis is more difficult still (Figure 2).

Figure 2. In order to effectively contribute to the advancement of athlete performance with technology, we should: 1) collect data reliably, 2) analyse the data accurately, 3) predict future outcomes, before 4) prescribing the ideal solution(s).

If you’re anything like me – wanting to use every advantage at your disposal – effectively integrating scientific literature and collected data feels like a daunting prospect. In my opinion, this challenge can only be met by the correct interface between man and machine (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Whether we like it or not, the merging of machine and human intelligence continues as we strive to advance our understanding of how to optimise performance.

The machine is needed to integrate big data with the most recent understanding and models. Solving the optimisation problem is also important. That is: what is the most effective session that will maximise my physiological adaptation? Realistically I doubt the human body is that specific. There will be a range of sessions that have the same, or a very similar, physiological response. There are many ways to skin the proverbial cat. But, there is no machine that sees the athlete walk into the session limping, or with particularly tired eyes. Or decides the surface is too slippy or wet to be able to safely complete the prescribed session (Figure 4). Well, not yet anyway! Perhaps most important is the belief the athlete has in the session. The conviction that this is the best session for them. The coach’s human touch is composed of thousands of factors and emotions. I’m convinced the best solution outright is for programme delivery to be machine-prescribed, human-deduced and delivered.

Figure 4. The myriad human aspects of importance within the athlete-coach relationship.

There are plenty of options out there to record and analyse our data. For a while I’ve been interested in combining this and other data inputs with our best understanding of human physiology to offer training prescriptions. Over the past few years I’ve encountered a few businesses working towards this goal. For me, it’s crucial that the people at the centre of the project are human physiology experts — to ensure that the platform is grounded in the most appropriate science taken in the correct context. I believe it’s also essential that the barrier to entry is as low as possible; that the models can function using inputs from the least number of gadgets, the profiling can be done as easily as possible and human perception is taken into account. As someone who is not a computer scientist, I want to see Artificial Intelligence (AI) used to drive genuine and valid continuous adaptation of training programmes, producing results that can be validated and ingrained in a constant feedback loop of progress. And finally, I’m fascinated by the challenge of working with scientists and programmers to develop the interface between the AI produced suggestions and the human coach.

Athletica ticked these boxes for me, and more. It’s the product of years of work. The combination of expert scientific understanding and brilliant programming. It has a library of thousands of sessions that are arranged into constantly adapted programmes by clever AI. AI that takes into account your initial parameters, your training data and the human inputs of perceived exertion and post session comments to constantly keep an athlete on the optimal training path. Most importantly, it soon will bring these features to coaches to empower them to be the best they can be. That is why I am excited about the future of training for endurance sports. And, the role Athletica and AI has to play in it.

Written by: Alistair Brownlee