Alistair Brownlee getting ready to go for a run.

The other day, I was happily driving along the motorway (Interstate, if you’re in the US), enjoying the view after a great day of training on a cold winter’s day in Yorkshire. Oddly, I’ve always enjoyed driving. As I sat still, warm, and unable to focus on anything else, my relaxed state was rudely interrupted by a chorus of infuriating sounds and flashes from my car. Hang on a minute, I thought. No longer was I in a happy state of contentment, but instead, catapulted to the same state I find myself in when I get nagged to take the rubbish (read trash, my American friends) out.

The offending sounds alerted me to the fact that I wasn’t paying due attention to the car. Or, at least, that’s what it thought. The car, driving itself at this point and seemingly using some kind of sorcery to gauge my attention, angrily informed me that the self-driving function was now disabled and would remain so for the rest of the drive.

While it wasn’t a pleasant experience, it got me thinking about the interface between humans and machines. No doubt, this interaction had been rigorously thought about and designed to be as effective and seamless as possible. Effective, well it catapulted me out of my enjoyably reflective state. Seamless, not so much.

I’m no AI expert, so feel free to disagree, but I couldn’t help but think that this interaction is, perhaps, more crucial than the machine’s ability itself. This becomes particularly evident when considering that a mostly self-driving car may outperform a human driver in 99.9% of circumstances. However, it’s the remaining 0.1%, the most unusual and dangerous scenarios, that pose the greatest challenge. Making the leap to complete self-driving—and crucially, full responsibility—across that small gap could be a challenge even more significant than what has already been surmounted. As I relaxed into my heated seat, it prompted me to draw a parallel to AI-based coaching platforms.

At times, we get bogged down in what a system (AI or otherwise) can and can’t do. Instead, I think, we should be asking whether the AI system can perform that function better than a human. Coaching an athlete consists of many functions. Maybe the relevant questions to ask are: 1) which of these tasks can the AI perform better; 2) which ones can the human perform better; and 3) how do these functions interlink?

Importantly, how do we determine the use case range for an AI training application?

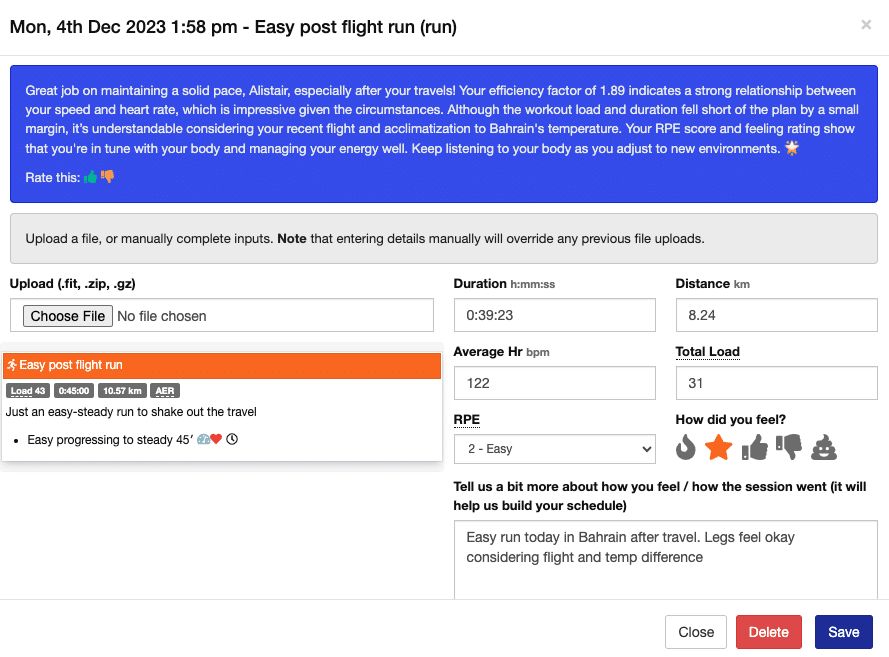

Alistair’s post-run AI Coach summary on Athletica.

All these questions are actively addressed through continuous product iteration, and one notable example is Athletica’s OpenAI Chat GPT integration. By using specifically formulated prompts inputted into Chat GPT, a textual synopsis of the workout is generated. This approach serves as a great way to explain the session to the athlete, aiding their understanding of the underlying principles. Personally, I’ve always held the belief that the conviction behind an intervention is as crucial as its physical components. Enhanced understanding fosters greater conviction, leading to increased efficacy and a heightened focus on delivering the session to the best of my ability. An idea that John Kiley found evidence for (Kiely, 2018). Research has also demonstrated the efficacy of using chatbot interventions to improve physical activity, diet and sleep (Singh et al. 2023).

I don’t think Athletica’s GPT integration will, or should, replace human interaction between coach and athlete. Instead we should constantly be looking at how we can maximise that interaction.

Returning to the car analogy; it’s akin to the vehicle kindly urging the driver to pay a bit more attention to the road. Perhaps validating this by stating the percentage of time their focus was not on driving, and providing context about how even a small reduction in concentration can statistically lead to a significant increase in accidents. It sounds like a brilliant idea to me. Someone needs to give it a try.